"Streaming: Sculpture by Christy Rupp" in the Fairfield University Art Museum's Quick Center Marsh Gallery is a must see. Artists that work with recycled trash as their medium will witness a master's hand with detritus and see work deeply endowed with the informed passion of a citizen scientist.

As you enter, there is an all-consuming 30' by 40' stock photo on the largest gallery wall. It is like an IMAX image of mountains of plastic to the horizon without a hint of the earth beneath. Rupp uses this image to attach her "Petroplankton," imaginative sculptural enlargements of micro-organisms at the bottom of the food chain, already compromised with micro-plastics.

Composed of steel and single-use plastic, each of these 27 microbe objects is cleverly hidden in the wasteland. They have names like "Black Pipes," "Drive Case," "Floss Blue" and "Computer Board." Wordplay is a tool Rupp uses to engage. This group name is based on the word

phytoplankton, replacing "phyto" with "petro." It is a series she calls "Moby Debris."

Welcome to Rupp's visualization of the problem of species caught in the crosshairs of survival.

The Marsh Gallery houses a tour-de-force selection of Rupp's work that is as esthetically astonishing as it is activist charged. The exhibition's catalog lists 78 works created from 2007 through 2023. There is potential dissonance when an artist uses trash to deplore trash. Rupp's works surmount this difficulty. Each delivers a deep message via a beautifully conceived messenger.

Mastery in felting, encaustic modeling, sculpting with steel and chicken bones, assemblage with colorful debris and wall- size cinematic collage backgrounds will all draw you in. Then you start reading labels and realize how deeply concerned and scientifically anchored each work is.

We talked about the “Nesting Pesticide Dolls” in the entryway. All the sections of a Russian doll are lined up, large to small, repainted with a color and the name of a pesticide in order of its percentage in the environment. “No more McDonalds for my family,” the guard continued, “every one of those pesticides is in their potatoes. If you leave some fries out for a while, they never get moldy.”

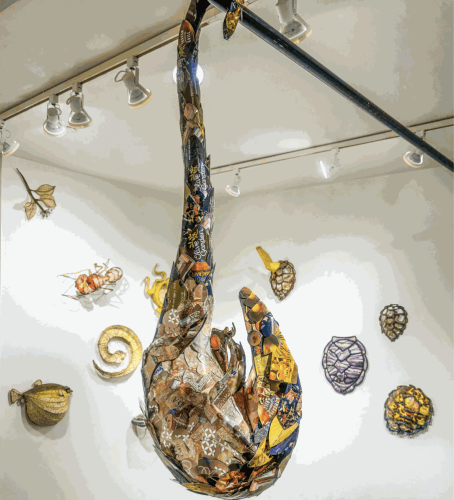

Rupp’s use of promotional credit cards to fashion sculptures of endangered fauna is her way of tying economic agendas to macro-ecological disasters and potential species extinctions. The lure of profit at the expense of subsequent ecological deficit is a dominant theme in her works. The credit card, gift card works include “Lifesize Manatee Skeleton” from her “Remaining Balance Insufficient Series” where the cards are all gold toned. “Two Pangolins,” the most trafficked animal in the world and critically endangered, are composed of metallic brown cards, and the “Swiped Series” a wall of frog skeletons of endangered amphibians is composed of cut up green-toned cards. They are as magical as they are alarming.

“Lemur 1” and “Lemur 2,” clinging to column tops as you enter the gallery, are Rupp’s most recent works in the exhibit. They are made from steel, toy chain saws and single-use plastic debris. The species, found mainly in Madagascar, is on the brink of extinction due to deforestation. Thus, Rupp’s ironic choice of detritus to fashion them.

Freestanding in the gallery are several works in the “Fake Ivory Series,” 2012, composed of welded steel, encaustic wax with transfers. Wax tusks, etched with hydro-carbon chemical formulas like scrimshaw, are a single-handed Brancusi- beautiful summary of petrochemical dependence, extinctions, oil spills and single- use plastic responsible for 80% of the ocean debris. The bones creatures use for defense, tusks and horns, are imitated in wax and decorated with death tattoos. These graceful works are central to the gallery and dense with meaning.

I asked the guard, "What it is like to be in the room with this exhibit?"

Then there are the “Moas,” 2007, based on extinct birds; these skeletal sculptures are composed of fast-food chicken bones, welded steel and paper. In a 2015 interview with Tiernan Morgan for the online zine hyperallergic.com, Rupp explains her process and intent for this series. To summarize, she explained that we care about species when they are gone, we care about extinction, so composing these skeletons from birds with five miserable weeks to live seemed appropriate.

The “Oily Turtles” series from 2007-2015 is one of the most poignant works in the exhibit. It is composed of steel, paper and encaustic wax. These are a set of shells only, attached to the wall like trophies, as if stripped from the creatures that wore them. One has ribs of dripping oil, squeezing out between all the shell sections. Dripping oil is a motif in many of Rupp’s collages, especially the series created in 2010 for a campaign to defeat fracking in New York State. “On Demand,” a 10’ by 38’ digital print from a 2019 collage, is one of the most powerful and threatening works in the room. Rupp parts an outer layer of green leaves to expose undulating silvery pipes that ooze oil. The manatee skeleton is attached to this image.

An early work, “Felted Oil Cans,” 2010, is a playful and mindful set of all the petroleum-based artifacts in Rupp’s home, faithfully replaced with felting. This combination of subject and material allows the viewer to imagine if petrochemical products were all replaced with biodegradable wool.

In the biologically specific rendered encaustic group, “Rainforest Sources of Bio-Pirated Western Medicines,”2014, we find out about plants and animals plundered for medical attributes. This is another case of economic gain causing flora and fauna loss that Rupp illustrates in gorgeous detail.

The “Snagged Series,” 2017, composed of plastic net bags, steel, plastic, fishline and paint is an artist’s playful homage. All these pieces could be displayed alongside the works they quote and be equal in importance. The artists celebrated by imitation are Frida Kahlo, Carel Fabritius, Louise Bourgeois, Jan Asselijn, Constantin Brancusi, Hieronymus Bosch and Pablo Picasso. Go feast your eyes and excite your art-historian hearts.

The series “Aquatic Larvae,” 2019-2020, composed of welded steel and single-use plastics are among the most entertaining works and grace the cover of the exhibit catalog. These works hit home as most of their parts exist in all our daily plastic recycle bins. There are white egg masses made from the pull- off white plastic caps of a pint box of half-and-half, yellow Styrofoam pieces and orange pill bottles. Rupp is brilliant with her use of materials and the depth of discussion she generates by using them.

Rupp will give an in-person gallery talk on Thursday, April 11 at 11 a.m. followed by an online talk streaming at thequicklive.com. If you are unable to get to Fairfield for this exhibit, the gallery has prepared a delightful virtual tour online where you can fly around the room and get nose close to the works at fairfield. edu/museum/exhibition.

Rupp’s book, “Noisy Autumn, Sculpture and Works on Paper” a career-spanning monograph published in 2021, is available in the Fairfield University Quick Center Box Office. The title is a word play response to “Silent Spring” by Rachel Carson in the year of its 60th anniversary. Rupp’s book is a treasury of images with essays by Lucy R. Lippard, Carlo McCormick, Amy Lipton, Nina Felshin and poems by Bob Holman. Rupp laces the image-laden pages with quotes selected with the same deliberate aplomb she chooses her materials. The quoted writers include Rachel Carson, Bob Dylan, U.S. Congressman Steve Stockman, Maude Barlow and Slavoj Žižek.

The final chapter in Rupp’s book includes a poem titled “The Solution” by Holms. It starts with the line: Folks, art is a job to renew vision...

ending with:

The solution in Art

is to play your part

hereplied,"Itcausesgreatself-reflection.Iaskmyself,'Whatismy part in this?'" I imagine all visitors will share his reaction.